Indoek Interview

How did you two first meet?

Wayne Gunther: I was a fashion photographer. Basically I met Donna in Chicago at Elite Model Agency, she was pretty much booking the talent there. I thought she was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen in my life. I tried to take her out a couple of times to no avail, but that was basically where we met, in Chicago. I was in there booking models for a couple of catalogs or little ads that I was doing.

Donna Gunther: I’m going to interject and say that there’s a lot that people don’t know about us. They have no idea that Wayne was a highly respected commercial fashion photographer. He had a studio in London, he worked in Milan, New York, Chicago and all over – and I wasn’t actually a booker at the agency, my title was Art Director, I developed models and created marketing materials for the models and the agency.

We’ve always been about seeing, creating and sharing beauty, sensibility and dreams. In the past we did it with models, merchandise,

locations and light, these days we do it with objects, environments

and imagination.

Wayne used to pull a chair up next to my desk at the office in Chicago and talk to me about his dreams – about building an adobe in New Mexico and the life he yearned for in California. He used to come out here surfing all the time. He shot jobs out here. He caught my imagination.

When did you guys hit it off and decide to move out here?

D: About four years went by. One cold February day in Chicago I was waking down the road thinking about a conversation Wayne and I had shared and literally bumped into a photographer who Wayne stayed with when he was in town. I asked if they were still in contact. “Yeah, I got off the phone with him 10 minutes ago” was the reply – so I scribbled down my number and asked him to pass it along. Wayne and I proceeded to have a month-long phone conversation. He’d call me from all his shoot locations. With nothing to loose we laid all our hopes, dreams and views on the line. Then, just before leaving for a shoot in Mexico where he’d be unreachable, Wayne asked if I’d meet him someplace if he sent me a ticket. I agreed without a moment’s hesitation. We decided on a date and to meet at the gate, he wanted the destination to be a surprise. His last words were for me to look out for the FedEx package with ticket inside – which, believe it or not, was stolen out of the lobby of the building in Chicago where I lived. With Wayne out of reach I got on the phone and hustled to figure out where the destination was, what airline I was flying on and eventually replaced it.

W: Something you could never do now – they would never tell you what plane you were supposed to be flying on now. This was in 1990 or some- thing like that.

D: So I replaced the ticket and got off the plane in New Mexico for a 7-day trip that ended being 9 days. Wayne started booking me as his photo assistant. First job was Hawaii. I got on the plane, met Wayne in Hawaii, did the gig and basically never looked back. Next was a gig in New Orleans, the plan was to drive there. We met in California and hung out at Wayne’s house on Crestmore in Venice – it was decorated with Ranch Oak and Monterey Furniture, a few Hawaiian nodders prominently placed on a shelf and a 1960s Hansen in the corner. We drove to New Orleans, the job fell through so I got on the phone – with my connections and his portfolio started hustling up jobs. That trip turned into a nine-month adventure criss-crossing around America in a Honda, doing jobs along the way.

W: We did 30,000 miles.

D: We did 30,000 miles and came back with a bunch of cash and the realization that we could spend our life together. It was an incredible time and an incredible road trip. We were shooting photography jobs, meeting with fashion clients and looking for vintage surf and Hawaiiana items everywhere we went.

W: We even picked boards up in Pennsylvania. We were picking things up everywhere.

D: Wayne’s focus was on the surfboard stuff and I was buying things for the California home I hoped we would one day share. Everything got shipped back to Chicago or we shipped it here.

Eventually we got to Chicago and picked up my car, tagged-teamed to California and found ourselves a little house in Mar Vista. It was an incredible time and it was the foundation of this whole business, this whole life we share.

W: We had a 14-foot paddle board standing outside the place on Chase in Mar Vista. We put lights around it and made it into our Christmas tree. People came from everywhere to photograph it. This would have to be about 1992. The whole house was decorated with our collection of surf stuff and Hawaiiana. We had about 100 vintage Hula Girl Nodders, made in Japan in the 1940s and ‘50s, and we had nine hula lamps with the hips that moved. The whole place was kind of crazy, it was just what we did back then. It was fun.

D: We started spending more time in California and the collection was growing, I turned to Wayne and said, “Look, you cannot bring any more things into this house unless you start making room by selling some.” So we started selling, continually upgrading – selling one piece and bringing in another. Honing our skills and our collection.

How did you end up on abbot Kinney?

D: We actually moved to Abbot Kinney as photographers. I was shooting kids fashion at the time, that building was a warehouse when we moved in. There was a ceramist who also worked as a psychologist working out of there. The place was divided into lots of small rooms and had shag carpeting everywhere.

W: She had massage therapists in there too.

D: Abbot Kinney was a wacky mish-mash of everything. There was a car wrecking place across the street where Acutonix is, a liquor store where Wabi Sabi is – the liquor store smelled so bad of cat urine that nobody could go in there. It was disgusting. The place really just reeked.

W: We never knew what was really going on in that store. There was a photo lab upstairs from where The Stronghold is now, people were always going in and out, they were selling what was then considered illicit stuff, the same stuff that’s now sold legally a few doors down. Behind our building there was a crack alley, there were helicopters and semi-automatic going off every other night.

D: We could handle all the craziness – we were from cities. We put up with the chaos as a trade off for the space, the cheap rent, the creative community, the quiet days and the short walk to the beach.

W: It was the last blue collar place you could live by the ocean. Nobody wanted it in those days.

D: Our side of Abbot Kinney, was zoned “artists-in-residence” but our building hadn’t been converted yet, so we made the necessary improvements. To be an artist-in-residence building legally (at least in those days) there were a number of building codes to meet and the tenant either had to be a true artist working, living and selling goods out of the building, or an antique vendor. We made a little apartment in the back, we had a photo studio in the center with accordion doors so we could open it up to the back if we needed to. And we had a reception area in the entry. We put a screen door on the front, a couple of iconic things and white curtains in the windows.

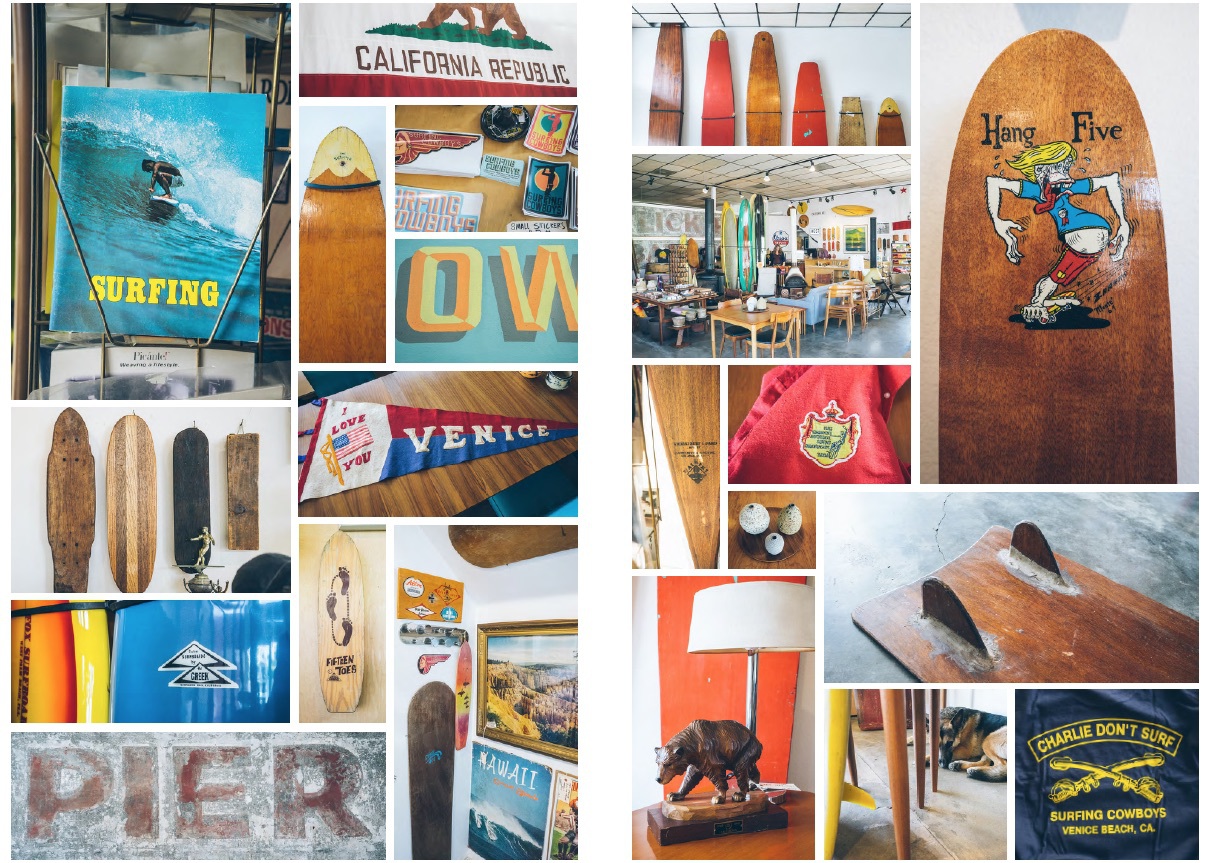

That front section always had surf and Hawaiiana stuff on display. Ukuleles, vintage Vespas, Navajo rugs, we had an Indian motorcycle hanging in the window. Things we liked. People used to go to Capri, the restaurant next door and they would knock on the window or they would look through the screen door and ask if stuff was for sale – that’s how we met a lot of our first customers. We slowly started selling things out of there while we were still working as photographers, shooting and living in the back.

W: The first day we ever opened the doors as a store was on one of the street festival days in September. I had a booth out in the middle of the block. The street festival was very different back then, it was much smaller and it was mostly local artisans selling stuff. A women came up and started talking about her house in Hawaii while I was trying to help other customers, I said “Oh, if you like Hawaii go and see my wife over there in the store.” We’d literally just opened for the first time that day. The woman walked in and basically bought everything in the place.

That was our first day. Our first sale was about $3,000.

D: We were thrilled. Our primary objective was to make a living and enjoy doing it. We were picking up things we liked, we marked them up at what we thought was a reasonable flip and we sold them off. To put this in perspective this was before Craigslist, before eBay, before the American Antiques Road Show – certainly before The Pickers, before any of that. We knew what we paid and flipped it – and that’s how we built this business.

When did you make the switch from photography to full on investment in the shop?

W: I think it was a year before 9/11. We had been traveling so much. We were on the road shooting constantly. It became total wear and tear on our asses. We decided to try and make a go of staying in LA – which is you know, committing professional suicide. Because in those days there was no fashion here, it was t-shirts and wetsuits. I was photographing in those days for places like South Coast Plaza, Fashion Island and Century City. I’d see these huge billboard ads that I had done. But it was not very exciting work for me. It was a way to be able to go surfing. We just kind of segwayed out of one and into the other. It was kind of a seamless thing. So we committed professional suicide and I got to go surfing everyday.

D: We just winged it. The people who supported us and helped put us on the map and gave us the courage to keep going were mostly in the industry, prop stylists, designers, and locals. Ralph Lauren bought stuff from us and shipped it to their stores. Abercrombie & Fitch bought a bunch including one of our vintage Vespas which they put it on the cover of their catalogue with these gorgeous twins on it. The team from Hollister (before they were Hollister) were in the shop. We sold to everyone from Diesel and Restoration Hardware to Tommy Bahama and Balenciaga. Buyers came to us as a destination, their purchases encouraged us to keep our dream alive.

W: For us it was just our way of doing things, we had no idea that we were creating a whole new look that nobody had actually done before. That’s what the fashion brands do by definition, find the hip new places and hip shops, check them all out and buy inspiration. They would be in Austin before anybody just seeing those little shops there.

D: Remember, this was a different time. No one had an iPhone or used Instagram. Nowadays companies do research online, but back then we all did it by going places. Like I was saying, the Hollister guys came in before they were Hollister asking about printed material with surfing stuff on it. We just sold everything as we went. I was often asking, “Well, what are you looking for? What do you need?” I would keep lists and call people when I found the right stuff for them.

W: In many ways, we exchanged the photography aspect of finding cool places to finding really cool pieces. It was still about a hunt and an aesthetic, but now it wasn’t to take the actual photograph or create the essence it was, in many ways to help these companies take their photographs, because they were grabbing all this stuff and putting it into a set or a new environment.

D: We were basically art directing a movement, without knowing it. Offering an extension of what our house and dreams look like. And we’re grateful that the sharing has helped us to have the life we wanted; we got the dog, bought the house, and we’re still traveling, never looking back. Somewhere in there the Venice housing boom hit and we went on overdrive.

What changed for us along the way was that we started to realize that we were helping all these other brands do some of what we should be doing for our own brand. At that point we started holding some stuff back with the idea that we would eventually be approached by a bigger entity to grow this into its next level. Our business has evolved a lot, we’ve learned a lot, the roots go deep and we’re still kind of doing it the same way. If it’s not enjoyable, interesting or challenging then we don’t do it.

W: We’re not the same store that we used to be on Abbot Kinney. We’ve kind of grown up. We couldn’t keep selling all things to all people. At one point we realized we needed take-aways for tourists and people that wanted to buy something from Venice and our T-shirt became that thing. But when we moved here, we kind of upped the ante somewhat. We’re not a surf shop, we’re not a furniture store, we’re a bit of everything. Now I feel we’re selling the best that we can find. The true vintage beauties, interesting, beautiful furniture and iconic pieces that we would happily have in our own home. We’ve become more selective in what we do and what we sell. It keeps us more interested

and interesting.

What are some of your favorite stories behind some of the pieces here?

W: There are a lot of great stories. It’s not like one story jumps out. The beauty of these boards and this furniture is partially in the lives that they’ve lived. If they could talk, imagine the stories they’d tell. We have a collector story, but each one these pieces has another kind of story. I look at a paddle board like the Skipper there and I see a father making that for his son or his daughter back in the 1930s. I can see him with his Popular Mechanics magazine, his Tom Blake pattern centerfold open. I see him working the construction out in his garage, then painting it and writing skipper on the top, turning to his kid and saying, “Here we go, let’s go surfing – it’s just like your old man’s!”. That and that kind of stuff is wonderful to me. That’s folk art.

D: I look around and see loads of individual objects that we could talk about, but I’m most excited I think by overall, collective inspirations and juxtapositions. I look at the history of surf captured within these walls. Same thing with the ceramic. All this ceramic was made in ‘60s California at a time when people stopped wearing gold and silver jewelry and started wearing brass. At this same time artists were taking clay and rather then shaping traditionally defined beautiful things, they were making natural, rustic, earthy pieces – they were breaking rules and coming up with new forms. There are rules of design that have been broken all over this shop – both in the objects and their placement next to each other – those are the stories I see that excite me the most.

W: We have a surf aspect to what we do, but pretty much everything here has a story. Look at the Navajo jewelry. The Navajos were always trying to work out what the white man wanted, what interested him, what they would buy. They would make rugs that had cattle on them and trains and trucks – evidently things that the white man placed importance on. In the 1930s a guy called Fred Harvey laid railroad lines across the west and set up trading posts along them, he encouraged local Navajos to create merchandise for the travelers from the East. They put arrowheads, birds, eagles, stuff like that on the jewelry – offering the travelers an opportunity to buy a piece of the romance, the myth, to this day these are referred to as Fred Harvey pieces.

D: On that note we’ve always been a bit of a road stop ourselves. This whole business was influenced from our time on the road. When we moved into that space on Abbot Kinney I hired an old-school sign painter and said I want it to look like a road stop in New Mexico, but cooler – we’re near the coast – we’re selling California. We were a road stop to our personal aesthetic. On the side of the building it said, “Purveyors of Beach Culture and California Lifestyle: Hawaiiana, Mid-Century Modern, Rare Cultural Icons and Cool Euro.” That was back in 1993 or something. That’s what we always were and that’s what we still are, we’ve evolved to a museum-like level, and the range of merchandise has shifted but everything here is for sale and there’s a take away, so that everyone can leave with something.

W: I think the name, “Surfing Cowboys” also conjures up kinder gentler times in a place not so long ago that was desert and ranches. I love the mind’s eye view of seeing guys get in the backs of their old pick up trucks in the 1930s with a giant redwood balsa board that they bought at the pacific system homes or they made themselves and taking it down to Rincon. In those days these guys knew each other because there was maybe 100 of them surfing back in the ‘20s and ‘30s, and in the ‘40s maybe 400 in the whole of California. So a lot of them knew each other personally. They’d go on amazing trips and do amazing stuff.

For me your shop on Abbot Kinney was such an iconic location that I associated with Venice. How did the move to Mar Vista

come about?

W: Wallpaper magazine called us the best store on Abbot Kinney a while back. They talked about the whole designer mix in the Beverly area, and they said there was “a way out west rival on Abbot Kinney… best is Surfing Cowboys.” For us this was huge. We’ve always respected Wallpaper Magazine. Details called us the “Best men’s store in LA.”. So we got hit with three titles, none of them that we really wanted because we didn’t want to be known as just a mens store, but it was kind of fascinating. Getting back to Abbot Kinney it was this old outpost that people would just drive through with the windows definitely up and the doors locked on a short cut to Santa Monica. As a few shops started opening up, people saw that there was four-hour parking on the street and would brave it to Hal’s, perhaps walk a block or two or drive because we were open or Capri was open – Jonny B. Wood was open or one of the four or five other shops that dotted the street; and then it started to fill in.

For a period of time, maybe five years, Abbot Kinney was a magical street with like-minded people that still didn’t get as much traffic as Melrose, Robertson or Montana. We were all really aware that we were in an amazing place and time. And then the NY Times wrote about it, the LA Times wrote about it, and before we knew it there were realtors and developers sniffing around. Wabi Sabi opened and brought valet parking to the street. That to me was the beginning of the end. Wabi Sabi killed it. Gjelina came in and put another knife in its back. Then before we knew it everywhere had valet parking, the food trucks showed up. It just became an impossible street where the masses could get drunk and eat bad food.

D: I think that the earlier, slightly rougher time worked because there was a sense of camaraderie. We were all in it together.

W: We were trying to make it safe without making it trendy. We were aware of what trends do. We’d seen it on Houston Street in New York and in the Lower Village. I’d seen it in London and before that on Rush street in Chicago to a certain extent. We didn’t want that to happen, but it was kind of like trying to hold the tide back. Developers don’t allow evolution to happen organically and naturally. They want to change it today, not tomorrow. When you try to create something that is hip, it won’t be. It’s just the way it is. The thing about places that become fashionable is that by definition, they’re going to become unfashionable.

D: And now in retrospect we can look at Williamsburg and all the other places that have been hit by so-called “development”. It’s like a bad joke. When the street had turned everyone kept going on and on about the “community” in Venice and we kept saying we didn’t see the community anymore in Venice. There was once a really great community, but that community started disappearing – it belonged to a moment in time when people were coming into our store, to the street, bumping into each other, know each other or be interested in meeting one another.

W: We could have stayed on Abbot Kinney. We could have had a smaller shop. We were offered places. The developer that got our place was absolutely shocked when we said, “See ya!” For us it was over. I don’t mean that in a nasty way, it was just that for us it made no sense being there anymore. We could have stayed there, but it would have become a business that neither of us were passionate about, with the pressure of a huge overhead.

D: Our shop has always been our home base. It’s like our version of corporate headquarters. We do research, we take photos, we bring stuff in and clean it. Abbot Kinney became a high rent retail street. Because of everything happening there, it was like being on Broadway in NY or something. We could have opened a shop specifically targeted for that street. But that wouldn’t be the shop that inspires us to go in for work everyday. That’s what we moved over here [Venice Blvd] for, this is our nucleus a connection to what we’ve always been and a jumping off point to what we will next become.

Are there any particular parts of Venice’s history that are endearing or special to you?

W: I first came to Venice in the ‘60s. I flew into Boston with a friend and hitchhiked to Cleveland where we had a place to stay. We were bored there, we didn’t have a lot to do and we didn’t have any money. I had 27 pounds with me that It took a year to save. We went to the freeway and just started hitch-hiking. We ended up down in Laguna Beach. We both got a job at the same restaurant. We worked for a couple of months to make some money and then just cut loose and ended up in Venice. I was on my own by then, the other guy went to Mexico or something like that. I ended up sleeping rough on the beach. Again, Venice was a very different place, there were a lot of youngsters there. The beats, the surfers, writers and just a fantastic mix of people. Somewhere in my recollection there was a council with a gay guy as the head of it, which was virtually unheard of in the ‘60s, it felt like a free, liberated place where anything went. I rarely saw the police but I rarely saw any real trouble either.

There was always a freedom here, even during the ‘60s there was a huge gay population. It felt remarkable in a country that at that particular time was very uptight. Abbot Kinney was an entrepreneur, he had the amazing idea that if you build it they will come – and they did for a while. Then it ran into ruin. You read in Bukowski books about Venice and people having chickens, wild ducks in the yard and people crashing all over the place. Interesting and creative things were going on during those days. That’s way back when Abbot Kinney was West Washington Blvd. I think it’s always had a history, it’s always been interesting. I think the fact that artists congregated here was great. It was just a place where surf, poetry, art, cheap rent all existed together. Blue collar drunks hanging out in a place by the ocean, a paradise.

D: I try to see Venice with a fresh pair of eyes and see it for what it is, because I don’t want to be caught in comparison. We shouldn’t do that to ourselves as we grow older. Nothing stays the same. Everything changes everyday. Find what you can enjoy, leave the rest, and move on.